Many people get enough hours in bed yet wake up tired. Understanding deep sleep and sleep stages is essential for true restoration, mental clarity, and emotional balance.

One of the most confusing experiences people bring into psychiatric care is this:

“I’m sleeping all night — but I wake up tired.”

They’re not exaggerating. Many track their sleep, spend a reasonable amount of time in bed, and even fall asleep quickly. On paper, everything looks “normal.” Yet during the day they struggle with focus, emotional resilience, motivation, and mental clarity. Coffee helps briefly. Willpower works for a few hours. But by mid-day, something feels off.

This is where psychiatry often needs to look beyond how long someone sleeps — and focus on how the brain sleeps.

Sleep is not a single state

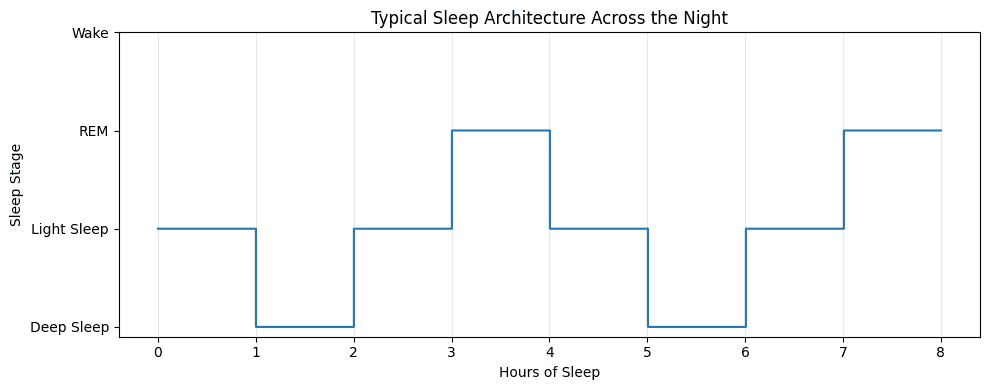

Sleep is made up of distinct stages that cycle throughout the night: light sleep, deep (slow-wave) sleep, and REM sleep. Each stage serves a different biological purpose. Deep sleep, in particular, plays a critical role in physical restoration, immune regulation, memory consolidation, and emotional stability.

Research consistently shows that insufficient deep sleep is associated with impaired attention, slower cognitive processing, mood vulnerability, and increased stress reactivity — even when total sleep duration is within recommended ranges. In other words, the brain may technically be asleep, but it isn’t fully restoring.

This is why people can wake up after eight hours and still feel unrefreshed.

A scenario I see often in practice

A patient comes in reporting chronic fatigue and cognitive dullness. They’re functioning — working, exercising, socializing — but everything feels harder than it used to. They say, “I sleep seven to eight hours every night. I don’t understand why I’m so tired.”

When we look closer, a pattern emerges. Their sleep is fragmented. They spend long stretches in lighter stages of sleep with minimal time in deep sleep. Sometimes this shows up on wearables; sometimes it becomes clear through careful history: frequent nighttime awakenings, early morning cortisol spikes, or difficulty reaching deeper sleep after stressful days.

They’re not sleep-deprived in the traditional sense. They’re recovery-deprived.

Why deep sleep gets disrupted

Deep sleep is especially sensitive to stress, circadian disruption, and nervous system hyperarousal. Chronic psychological stress, late-night light exposure, irregular schedules, alcohol, inflammation, and certain medications can all reduce slow-wave sleep. Over time, the brain prioritizes vigilance over restoration.

From an integrative psychiatry perspective, this often explains why people feel “wired but tired” — exhausted during the day, yet unable to achieve truly restorative sleep at night.

Importantly, this isn’t a failure of discipline or sleep hygiene alone. It’s a physiological state that requires thoughtful evaluation.

Why more time in bed doesn’t fix it

When deep sleep is compromised, people often try to compensate by spending more time in bed. Unfortunately, this rarely works. Sleep architecture doesn’t improve simply because someone lies down earlier. In some cases, extending time in bed without improving sleep quality can actually worsen insomnia and reinforce frustration around sleep.

Restoration depends on sleep efficiency, stage distribution, and circadian timing, not just duration.

How psychiatry can approach this differently

A more precise approach to sleep looks at the whole system: stress physiology, circadian rhythm alignment, medication timing, metabolic factors, and nervous system regulation. Sometimes small shifts — light exposure timing, evening arousal reduction, addressing nighttime cortisol patterns, or supporting underlying inflammation — can meaningfully improve deep sleep without adding sedating medications.

This is where integrative psychiatry becomes especially valuable. The goal isn’t to knock someone out. It’s to help the brain feel safe enough to drop into restorative states.

The part patients often find most relieving

When people learn that their exhaustion makes biological sense, something changes. They stop blaming themselves for being “lazy” or “unmotivated.” They recognize that their brain has been working without sufficient recovery.

Sleep quality is not a luxury. It’s foundational to mental health.

And deep sleep — not just time in bed — is often the missing piece.

Future Psychiatry is a concierge practice in New York City specializing in integrative psychiatry, anxiety treatment, and holistic mental health. Founded by Jafar Novruzov, PMHNP-BC, the clinic provides luxury, evidence-based psychiatric care designed for long-term wellness.